Words by Brit Parks

I have seen an image of one woman blowing smoke into another’s mouth in my dreamscape. I have seen Cubism fall backwards to whisper in the ear of Surrealism to remind it art is a history of metaphorically blowing smoke into another, morphing to inform. There are aged-ancients at work in Melissa Kime’s paintings. There are women stretching their stomachs to hold birth. There are women stretching their skin to hold each other.

And the hair.

They are sharing their hair like a breath of smoke into each other’s mouth. It is entangled, intwined, inseparable. Kime has given her paintings a narrative deeply rooted in a belief system racing through her veins. Her paint is layered with brushstrokes that are hard pressed and then soft forgiven. Her color palette is born of this admixture. Kime steeps herself in the history of women with powers. Authenticity is often an overused term, however, I consider it a commitment you cannot live without which holds true in this case. Kime loves to recall Ophelia’s fate. Her version makes me feel like she sees a little of the drowning and guttural victory of her in each new woman she gives birth to in her work. I feel like I have risen from a lake when I endeavor to ask her where it has all evolved from in her mind.

Brit Parks: I know you work with the complexities of women in a historical and contemporary context. Can you speak to how you filter all those time frames in your inner language to create visual representations of these ideas.

Melissa Kime: When I was a child I was often taken to the American Museum in Bath, England. We watched reenactments of battles between Native Americans and cowboys. However, my favourite part was wandering through the museum displays of the oldest patchwork quilts in Britain. I loved the stories you could see stitched within them. It reminded me of being young and watching my mother at work reupholstering ancient tapestries and rugs. I would watch the ladies at work; crouched over the floor with backs bent meticulously stitching, sewing, fixing, and mending. Their chat and conversations weaved their way deep into the structured folds of the fabrics. It in turn, hemmed their generations’ experiences in between the ancient histories that they were preserving. Perhaps, subconsciously this fond memory of women working fervently together reminded me of generations of females in the past. They were united through needle work, a tradition which is often passed down. I enjoyed the camaraderie as it was special and unique.

Later as a teenager, my Mother began working as a tour guide at the American Museum. I loved the sentimental tales she came home with of how patchwork quilts had names and letters stitched on them. They were made to immortalise and remember the people that had died or who had made the quilts. For example, the Baltimore Album Quilts , which were made for somebody living in Baltimore in the years 1846-1852. This act of remembering or preserving something in a quilt was described in my favourite book at that time, ‘Witch Child’ by Celia Rees. It follows a young Mary Newbury who had to flee and travel to America while her beloved Grandmother is falsely condemned, tortured, and hung as a witch. Using the literary device of a found document, the book is based upon the real diaries found of fearing girls accused of witchery in the 17th century. In this particular story, Mary was frightened that the witch hunters would find her diary and then in turn hang her. She stitched her sacred diary between the lining of her quilt. Many women and girls did this at the time which made the quilts crucial to their safe keeping and well-being. My dad gave me a patchwork quilt for Christmas 2017 and I was overjoyed. At the time, I was struggling to find myself and I was quite anxious. Lying under the quilt, I would imagine the girls sitting and making it. I wondered how they felt and if they had gone through the same experiences that I was as a woman. The quilt became a comfort and reignited my obsession of collecting vintage. I then scoured for women of the past. I came across a French Catholic pendant from a magical antique shop in Lower Clapton, a neighborhood in London. Everything in the shop is piled high and you must dig to find the treasures. It’s one of my favourite places to go. I found a tiny 19th century locket of a young girl that had been made for her First Holy Communion. Her face struck me and she became a good omen. I also found a Victorian First Holy Communion photograph of a young girl named Madeline Milcent. I researched her and began drawing her as a major character in my work as she looks haunting but I find her so beautiful.

I combine archival images of historical women, my own autobiographical experiences, and the experiences of contemporary women on the subjects of trauma and the persecution that being a female entails. This compulsion to help females in my paintings was first captured when I watched a documentary about The Highway of Tears, a stretch of road in Canada where over 40 women and girls have gone missing or been murdered near the highway since 1969. Many cases are still unsolved and as many of them are indigenous, Canadian police have overlooked them. I hated this fact and it really upset me. I was also angry at the abortion laws in Ireland, Poland, and America to name a few and this all seeped in. It compelled me to want to do something for them and to fight for my generation of women. That’s one of my primary concerns and objectives as a female artist working now and I think it’s very important.

BP: Do you have a consistent process, as in do you do preemptive sketches for a work or does the piece evolve as you work.

MK: I have always begun my paintings by making drawings and small watercolour and acrylic paintings in my sketchbooks. To me the idea of creating a sketchbook is like making another world. It’s a place I can relive moments, disappear into or go back and look through to remember people and places. In a way, it feels like they keep people safe and close to me. My books are very personal and could also be seen as a visual journal or diary. I am writing through imagery as opposed to words. The drawings feel more raw and honest in some ways. I also seem to prefer their faces on the thin Moleskine pages. Perhaps this is because they are made more freely and on the impulse of feeling. I am somehow less guarded about making an image work. I often get frustrated when I begin to make a painting as the books and the content within are special to me and I can’t seem to emulate it in the same way on a canvas. Often this makes me quite upset and I am ruthless. Painting over and over paintings or the skeletons of works until I get the right likeness and feeling I want my women to convey.

BP: I know you speak extensively about your interest in the history of witchcraft rituals as a point of reference and inspiration. Can you talk about what aspect of this that you identify with personally and how that translates to your art.

MK: I am a Roman Catholic, I chose this at age six. I was then baptised and had my beloved First Holy Communion when I was seven. I adored the dressing up and the special sacraments that you receive such as my blue crystal Rosary, pendants of Mary, and Prayer Cards. You are also given an elaborate iced cake to congratulate you after the ceremony. All of these details made me recall and consider sisterhood.

My school was Catholic and incredibly conservative and strict but I didn’t hate this. I quite enjoyed the rituals there such as chanting the Saint’s names and celebrations of Mary where we would walk in processions of two to scatter wild flowers around the Virgin Mary’s feet to honour her. These acts of celebration don’t feel too dissimilar to me than some Witchcraft rituals of the past or even the present. Catholic folklore can be traced back to ancient Witchcraft traditions and English superstitions like hanging a Rosary on the back of the door to ward off evil.

I think saying a spell or making magic is like saying a prayer. They are not different to me. It’s a way of putting your hopes, wishes, and fear into something and perhaps a way of asking for help or guidance. I’ve done this all of my life from wishing on the moon to being at school where my friend and I would constantly practice Witchcraft at sleepovers. We did simple things like good luck spells. This act of female friendship made its way into what I think is my most ritualistic painting, “Light as a feather, stiff as a board” (Levison collection) which harks back to the film, ‘The Craft.’ It was directed by Andrew Fleming in 1996. Four girls test their powers with the classic sleepover game “Light as a Feather” which requires one person to lie on the floor while the others form a circle around her and try to make them levitate by chanting “light as a feather, stiff as a board.” Such supernatural pursuits make for a compelling depiction of female joy. It also causes one to revel in their own power with friends and creates an autonomous belief system for one’s self. That excites me. I do practice witchcraft, I like to behave like the girls in my paintings. I’m actively researching by joining a full moon monthly women’s circle that includes women from across the world. It’s meaningful as although we are all so different, we’re also not at all. I find that interesting about women’s friendships or the connection that females have. I think rituals pull that out of you and also connect you back to a sense of childhood like taking pleasure in simple things we see everyday but may take no notice of like a flower’s petals.

I do make spells and perform rituals by myself as well as with some of my closest friends. Such as a protection spell on one girl’s bed to New Years spells with others. It makes you feel closer, like a bond has been knotted and tied in place. It reminds me a bit of the brushing of another girl’s hair, it’s something I can’t really explain. It’s a feeling of being united with someone and that special integration and knot can never break.

BP: Visually, you employ varied methods of abstractions in your figures of women. There is stretching, morphing, pulling, bloating. I am interested in how this visual dialogue exists in your theories about painting in a more formal sense.

MK: My father used to collect Modern Art and he particularly enjoyed the work of Henry Moore. He would often talk to me about the history of Modernism and Post-war design and his appreciation for the abstraction of shapes where things are made simply yet still convey so much. It’s a bit like Picasso’s Cubist works. He would also show me pictures of art in books like Moore’s ink drawings with biomorphic shapes of women in tube stations huddled close to their babies. This reflected the contours of the Yorkshire Hills of his childhood. However, I cannot bring myself to simplify in my own work. I often over complicate paintings, filling in detail. I often simplify body shapes but not my faces. That wouldn’t suit the work in my mind. The information my Dad showed me from being young has become etched into me. We lived with his collections like Verner Paton heart chairs. The organic and abstract shapes were everywhere and now remind me of home and family.

I have always elongated the people in my drawings ever since I first picked up a pencil, it might be because I’m not concerned with accurate proportional drawing. I think it also reflected how tallness seemed to make more of an imposing impression on me even in my real life as I’m very short. I wanted the characters to be the centerpiece so they were remembered and therefore became the main protagonists of my stories. The bloating and pulling, the making of large dappled cavities inside of them reflected the nature surrounding them in the rest of the painting. I started doing this to tackle more personal but also universal issues surrounding body image in art. The human body is central to how we understand facets of identity such as gender, sexuality, race, and ethnicity. People alter their bodies to align with social conventions and to express messages to others around them. Many artists explore gender through representations of the body. I do it as a way of dealing with and or accepting my own body or the body image issues that I struggle with. Feminist artists of the 1960’s helped to reclaim the female body by depicting it through a variety of obscure lenses. Therefore, taking back control from the male gaze which has portrayed an idealisation of the female form throughout history. I want to try and find peace with how my body as a female works and looks. My women are distorted as they are trying to fit into themselves and grappling to accept their form as wholly female.

BP: What women in art resonate with you in terms of making similar work.

MK: The work that has influenced my paintings the most is Sofia Coppola’s film ‘The Virgin Suicides.’ It’s her 1999 melancholic adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’s novel about death in 1970’s suburbia. She captures it with ethereal shots of the Lisbon sisters isolated in their room. Their limbs are interlocking and folding into each other, over each other with piles upon piles of their hair wrapped around them. It invokes memories about those who have decided to leave us and those who are then left behind. It has a feeling of a loud misty shaped emptiness similar to the way you feel when you wave goodbye to somebody. It is also reminiscent of the stretch a summer holiday evokes and the extraordinary power of the unfathomable. It gives a glimmering insight into the unwholesome intensity of what being a girl really is.

Other artists and filmmakers I take inspiration from are Charlotte Salomon’s diariestic images and poetic texts from her book ‘Life? or Theatre?.’ Also, Jaclyn Bethany’s short film ‘The Last Birthday’ which is an experimental retelling of the last days of the Romanov sisters. Cate Shortland’s ‘Somersault,’ a film which came out in 2004 perhaps launched my interest in the fragility of coming of age. I also enjoy the work of painter Paula Rego. I like her stories and I am gripped by the way she speaks about her work and what influences her. I also look to Leonora Carrington, Louise Bourgeois, Frida Khalo, Evelyn Williams, and Jenny Smith whom I studied with at The Royal Drawing School. Although he isn’t a woman, I’m touched and intrigued by the worlds British painter Peter Darach makes. They are so honest and maybe even painful but so beautiful. They are a world you can vanish into – He is very moving.

BP: You have an adept method of layering oils and they seem to form a color palette in this way. Can you expand on how color functions for you.

MK: I actually think the layering of oils for me is an accident that came from not liking what I have just painted and then going to paint back over it again and again until the canvas is thick and textured but not at all even. I am unsure of my work a lot of the time and most of the time I don’t really like it. I am a staunch perfectionist and also very competitive with myself so I’ve destroyed work like that many times. However, I also like the texture of the worked surface that my canvas then gives. My worlds sit better on them and the colour glows more – It seems more raw or real. I try to look at quattrocento painters for compositional advice. My favourite painting is ‘The Hunt in the Forest’ by Paolo Uccello. I love the nocturnal landscape, the gothic undertones and how he used the black forest colours against the glowing horseman to pull them out of the image. I do this by plucking the women from my paintings and surrounding them in deep earthy or dark tones which makes them glow a bit. It looks like the icons of Mary in churches that are lit by hazy glowing candle light.

BP: You have fascinating titles, they feel like the first sentence of a book or a fragment of a poem in moments. Do you write extensively and pull from that or how do they materialize.

MK: Sometimes instead of a painter, I would say my role is to be a storyteller. When I go to make a painting there has to be a narrative and a protagonist otherwise it won’t work for me. I think of titles like that, they have to sort of hint at a rolling narrative that could spill over onto other canvases. That was how I was taught to make pictures by my parents. When we looked at paintings we would look for stories within them and when we went out on day trips I would be encouraged to draw everything that I had seen or done that day. This became my play time and I would play with the characters in my drawings probably more than I did with toys. The drawings were like reenactments I could keep reliving.

Storytelling was such a big part of how I learnt and how I have grown up and it also helps you to keep carrying that magic from childhood with you which is so often tragically lost. I have always written stories, plays, poems, and journals. I have also kept a written diary documenting everything almost obsessively to the point where my hand hurts and is red and raw. Looking back over these personal documents now I can see how they have helped in the formation of making titles. If somebody said something I needed to remember or I heard something in passing, I would write that down and that might become a title. Other times I pick them out of television shows, films or books. Lena Dunham’s HBO series ‘Girls’ or Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte has always provided many options. I really connected with those characters especially when I was the same age as Hannah, Marnie, and Jessa. I also felt like I could Identify with Jane from her ruthless and determined nature reconciled within. She has an otherworldly honest sensitivity that’s like the girls in my paintings. They are strong willed and stubborn to a point but they also have a magnified fragility. They have a seriousness brimming inside of them. I hope that shows when people study them.

I used to want my titles to be funny but I think that was a way of disguising the truth in my work. They aren’t funny and some of it is actually quite dark. In my painting, It felt like a bad flu, except it wasn’t it seemed the most honest and poignant way of describing four pregnant women. I really tried to method act within them and how I imagined that they would be feeling such as sick and scared. They could be worried that they wouldn’t be good enough. In reality, their pregnancy is so special and unique to one another.

BP: You have spoken extensively about concepts relating to being a Mother and how you feel this is a connection between women. Can you speak to your specific interest in that as a subject matter.

MK: This fascination started by looking at images of the Madonna and baby Jesus. I love Mary. She is incredibly human and I think as a female you can really identify with her. She was put in a really difficult position and maybe she didn’t want to become a mother or not then anyway, she was only 14. Similar to Drew Barrymore in the film ‘Riding in Cars with Boys’ made in 2001. Mary went forth regardless by doing what was asked of her. She went ahead with the ordeal and sacrificed herself and what she wanted to become Jesus’s Mother. I think that’s so selfless and brave. This selflessness echoes in the behaviour of my own Mum, she always puts us first even if we are difficult ( I am one of five.) She is very honest with all of us. I enjoy watching the relationship that me and my younger sister have with her, the Mother and Daughter relationship is so unlike anything else. I trust my Mum’s opinion so much and I talk to her everyday. In a way I think we are quite similar and sometimes I think she might look at me like she is looking back on herself. But my work is also about conceiving children, losing them, and not being able to keep them inside of you. There is a beautiful paragraph in the book that I’m reading at the moment, ‘The Familiars’ by Stacey Halls that really sums up the devastating fear of losing a child, a baby growing inside of you. Fleetwood Shuttleworth, a 17 year old who has already endured the tragedies of three miscarriages lies on her back pleading with her body to make the baby stay in her tummy and not fall out of her and down her legs. That desperate pure emotion is something that I am trying to convey and also to reflect again through 1960’s feminism and the backlash of the 1990’s which has still left women of this generation struggling to have control over our own bodies and reproductive rights.

Poetically, this was examined in Blue Valentine which was screened in 2011 and directed by Derek Cianfrance. It is a film about an abortion that should have gone ahead but didn’t. It got a lot of criticism about being too dramatic like most abortion scenes in movies usually do but what struck me wasn’t really the drama of it all. It was the scene of the quiet waiting room filled with girls. An anxious Michelle Williams chews on the hangnail of her finger, shuffling forward in her seat wondering what to do and what to decide, what she actually really wants. She went with her gut, jumping up from the medical table as the doctor began to prepare probing her uterus with his sterile instruments. I think we as women all know or have heard of somebody that has gone through this ordeal and has had to live with whatever decision they chose to make.

Lines of female lineage excite me too, it’s wonderfully fascinating to think of my life as an egg actually beginning in my Mother’s developing ovary before she was born. I was intertwined and wrapped in her fetal body as it developed within my Grandmother and her within my Great Great Grandmother. If I ever have a daughter she will now be existing inside my mum so It connects us all. I like to think that in some way we have all lived life through generations of women gone by. I like that.

BP: I am very interested in how you use hair visually to connect figures and also as a formal visual element. I know you talk about hair as a recurring representation of your formalist ideas on the history of persecuted women. I am not sure if this is a question, perhaps an observation and I am curious if that feels accurate.

MK: It is! I often use recurring motifs in my paintings that reappear over and over again like a kind of surreal symbolism. I link the women currently through plaited hair or menstrual cycles. It’s a bit like blood rights that could also represent thin strands of straggly hair that run between the girls legs. It reminds me of a part in ‘The Virgin Suicides’ novel where there is a description of an endless stench of girl’s hair tangled in the drains polluting the suburban streets atmosphere. It took me back to a job I had as a Lifeguard in Leyton where after women only sessions we would have to wash down and pull out thick black hair greased with shampoo and chlorine from the swimming pool showers. It was revolting and it stunk. It was here in Leyton that the plaiting started. We were a close team of girls but all incredibly different and from different walks of life but we connected so well. On occasion we would hide from the managers and lock ourselves in the disabled toilets, braiding each other’s hair or teaching different styles of braids to one another. Some girls were better than others but it made me think that the plait, a simple hairstyle was what was giving us that something special that we had in common.

Recently, my friend Lucy and I braided our hair together, her hair is very red and mine is dark but plaiting the strands around each other made the plait thicker, symbolising a bond or a friendship that could now never possibly break. Whatever direction we would take. Her red hair glowed as it ran through my dark roots.

The stitching method of the plaiting hair runs back again to the stitching of quilts and the image of my Mum at work and of a sisterhood never to break.

BP: Has isolation in London been a quiet space of contemplation for you to work, has it created a deeper place to think from. I know for some artists, myself included, it has felt like a very challenging period in terms of making.

MK: I think i have found it quite difficult but also it has been good for me at the same time. I have not been able to get to my studio in Hackney so I have been working from home. My partner, painter Archie Franks, has a small studio in his flat so he has kindly let me work there. I did need the space and time to reconsider my paintings. I had a solo show last year at C&C Gallery in Forest Hill, London. I was happy with the work but after it I felt like I kept comparing my new paintings to the works that were in the show and I just didn’t like them which stopped me from enjoying the process of painting in a way. This kind of block is normal for me. I just have to get through it and remember that I’m slowly going to come out the other end (fingers crossed) and I just need to be more experimental and less of a perfectionist.

I have been making a lot of drawings which I haven’t done really since I left The Royal Drawing School and started my MA at the Royal College of Art and that has helped me get to the arrival of a new subject matter about Avebury and the landscapes that I grew up in around my home county of Wiltshire. I have always been interested in the ritual stone circles created and how they connect with the supernatural like Beltane celebrations and the sacrificial connotations of being a May Day Queen which women participate in. I have heard that women were seen as more important in the Neolithic times because they were fertile and could carry on making a race. It is thought that they may be buried beneath or under the stones. They were given a place to lie and rest inside these monumental stone circles. I like this analogy. The stones look like Moore’s figures too, strong and powerful. I think that they are definitely female. I’ve just been given a new job teaching at the Essential School of Painting alongside my other teaching work at The Royal Drawing School and Richmond School of Art which will start in the Autumn so I have positive things to look forward to post lockdown!

CREDITS:

Images courtesy of Melissa Kime

In order:

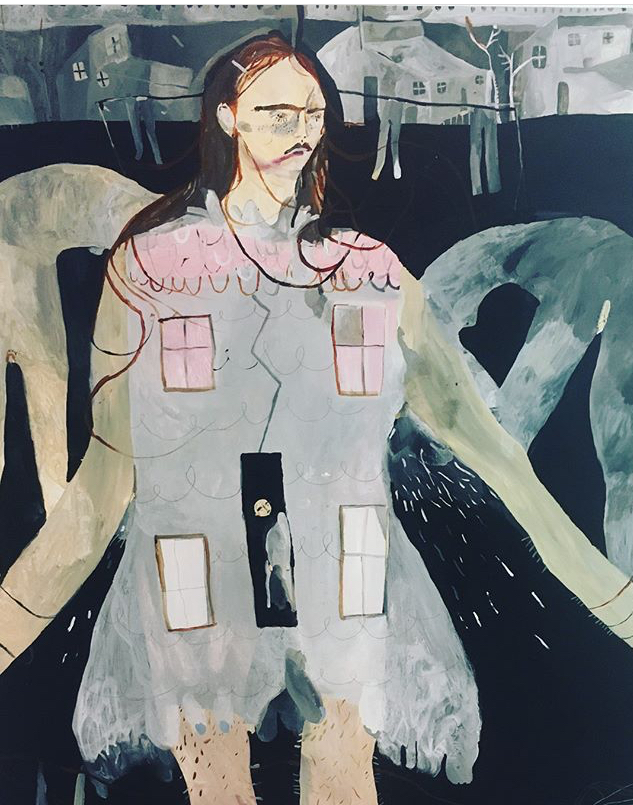

Ode to Ophelia wrapped up in her daisy chains, oil, oil bar and pencil on canvas, 2020

It Felt like a bad flu, except it wasnt, Melissa Kime, oil on canvas, 2019

light as a feather stiff as a board, oil on canvas, 2019

Tummy Ache, oil on canvas, 2019

Detail: It Felt like a bad flu, except it wasnt, Melissa Kime, oil on canvas, 2019

they were meant to be bubble gum Angels with golden hair that dropped sea blue tears, when they jumped they probably thought they could fly but Angels shouldn’t jump ever, acrylic on canvas, 2018

Future Land, acrylic on canvas, 2018